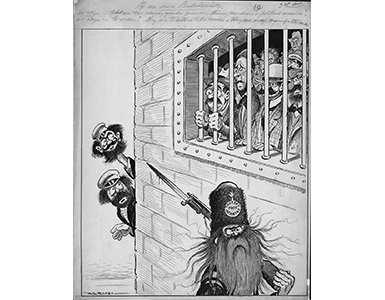

Improbable as it seems in retrospect, during the winter of 1918–19 the government and the mass media in Canada became convinced that the country was poised on the brink of Bolshevik revolution. Reds were everywhere conspiring to overturn the status quo, or so it was thought. The result was an attack of paranoia known as the Red Scare, when the government removed basic civil liberties and sent labour leaders and left-wing political activists to jail. The following is adapted from Seeing Reds: The Red Scare of 1918–1919, Canada’s First War on Terror, by Daniel Francis, published in 2010 by Arsenal Pulp Press.

“I AM A SOCIALIST AND PROUD OF IT. YOU CAN CALL ME A BOLSHEVIKI IF YOU WANT TO."

—R.J. Johns, Winnipeg strike leaderThe so-called Reds did not apologize for their radical views; neither did they accept the government’s right to suppress them. “I am a Bolshevist,” declared the Nova Scotia labour organizer Clifford Dane, “and I will warn these two governments that trouble is coming and the men will have what belongs to them.” The Reds fought back, with results that at times resembled a civil war. From their point of view, they were resisting an oppressive government that had taken away basic democratic rights of free speech and assembly. Indeed, the government helped to create a confrontational situation by providing in its repressive policies a rallying point that united factions on the left. The Reds felt themselves to be riding a wave, part of a worldwide movement for change. “To be a leftist in the atmosphere of 1917–1920,” writes the historian Ian McKay, “was to breathe a very special atmosphere, one in which a top to bottom reconstruction of society had seemingly gone from being a utopian dream to a real possibility.” Confident that history was on their side, radicals relished thumbing their noses at the authorities. Meetings invariably ended, as one in Toronto did in January 1919, with three cheers for “Bolshevism, Karl Liebknecht, the Social Revolution and Leon Trotsky.” (Liebknecht was a soon-to-be martyred German revolutionary.) No wonder a nervous government thought the Reds were plotting revolution at their meetings.

On a Sunday afternoon in December, three days before Christmas 1918, the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council (WTLC) and the Socialist Party of Canada convened a public meeting at the Walker Theatre, one of the city’s largest live-performance venues, on Smith Street near Portage Avenue. (The Walker, which opened in 1907 with a performance of Madama Butterfly, continues in operation as the Burton Cummings Theatre.) The 1,700 people who crammed into the theatre’s main floor and two balconies were in a boisterous, combative mood. “The remarks of the various speakers were frequently punctuated with deafening applause,” reported the Free Press, “particularly the references to ‘the coming revolution in this country’.” Perhaps the only person not shouting and clapping was Sgt-Major Francis Langdale, an undercover officer with military intelligence, who was too busy at the back of the meeting furtively scribbling down notes of what was being said.

The official business of the afternoon was to pass three resolutions. The first, moved from the stage by Bill Hoop and seconded by George Armstrong, both well-known members of the Socialist Party in the city, protested the federal Orders-in-Council imposed in September:

“Whereas, we, in Canada, have the form of Representative Government; and, whereas, Government by Order-in-Council takes away the prerogative of the people’s representatives, and is a distinct violation of the principles of democracy, therefore, we, citizens of Winnipeg, in mass meeting assembled, protest against Government by Orders-in-Council, and demand the repeal of all such orders, and a return to a democratic form of Government.”

“Whereas, we, in Canada, have the form of Representative Government; and, whereas, Government by Order-in-Council takes away the prerogative of the people’s representatives, and is a distinct violation of the principles of democracy, therefore, we, citizens of Winnipeg, in mass meeting assembled, protest against Government by Orders-in-Council, and demand the repeal of all such orders, and a return to a democratic form of Government.”

“The Order-in-Council is a negation of all that we have fought for and obtained for centuries,” Hoop insisted. “We do not propose for one moment to sacrifice those liberties—not for one moment.”

The second resolution accused the government of jailing activists “for offences purely political” and demanded the release of all political prisoners, meaning especially the many men who had been swept up in police raids since the passage of the Orders-in-Council. It was moved by the Reverend William Ivens, the forty-one- year-old editor of the Western Labor News. During the war the hierarchy in the Methodist Church had expelled Ivens because of his outspoken pacifism and anti-war activism. In response he founded the Labour Church, a non- denominational debating club that held meetings in halls and theatres around Winnipeg and was a focus for much of the left-wing intellectual ferment in the city. Fred Dixon, a labour member of the Manitoba legislature, seconded the resolution. Unlike most of the other activists with whom he shared the stage, Dixon rejected hard-line socialism. He was a liberal who was as suspicious of collectivism as he was of capitalism. Most socialists viewed him as a moderate, bourgeois reformer, yet his passionate opposition to the war and support for free speech placed him in the same camp with the Reds.

Third, the meeting endorsed a motion demanding that Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War end immediately. When the Bolsheviks came to power in Russia they negotiated a separate peace with Germany to end the fighting on the eastern front, a peace that was formalized in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, leaving the Allied powers affronted at what they considered to be the Bolsheviks’ betrayal of the war effort. With the outbreak of civil war in Russia, the Allies committed their own troops to help the White Army topple Lenin’s regime and, optimistically, to get the Russians back into the war. Canada had a few soldiers involved in the Caucasus and a few more attached to an expeditionary force sent to Murmansk, ostensibly to secure Allied provisions there. But the most significant Canadian involvement was in Siberia, where the Borden government promised several thousand soldiers.

he Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force, announced in August 1918, was not popular with the public, but so long as the war continued Borden felt it was justified. However, by the time the bulk of the men were assembled at a camp near Victoria, B.C., to prepare for embarkation to Russia, it was December, the war was over, and it was harder to explain why Canadian soldiers should be involved in a dubious foreign adventure that seemed to serve no national interest. Still, Borden was adamant the men should go. About a third of the soldiers were conscripts from Quebec. Resentful at having to serve in the army in the first place, they were a receptive audience for local leftists who propagandized against the expedition. By December 4, the British Columbia lieutenant governor, Francis Stillman “Frank” Barnard, was so afraid of an outbreak of violence in the military camp over the issue that he petitioned Ottawa to ask Great Britain to send warships to the Pacific Coast to keep the peace. Finally, on December 21, the day before the Walker Theatre meeting in Winnipeg, about 900 members of the force began to move through the streets of Victoria to the docks to embark for Vladivostok. During the march some of the men mutinied, refusing to proceed to the troopship. Officers ordered other soldiers to remove their belts and whip the recalcitrants back into line. Urged along at gunpoint, the mutineers eventually boarded the ship and the expeditionary force sailed for Siberia.