While waiting for my next book, Becoming Vancouver: A New History, to be published this fall -- delayed by the COVID situation -- I thought I'd introduce the project by telling some "tales of the city."

The death of James Cross last month took me back to October 1970. Not to Quebec, where the main events took place, but to Vancouver, where tragedy turned to farce.

Some basic background for those too young to remember. Cross was a British trade commissioner based in Montreal. His kidnapping by members of the revolutionary FLQ on October 5 fifty odd years ago marked the beginning of what came to be called the October Crisis. In return for his freedom, the kidnappers made different demands, among them the release from prison of several of their comrades. Five days later another FLQ cell abducted Pierre Laporte, a provincial cabinet minister. This led to the invocation of the War Measures Act by the federal government, the deployment of armed troops in the streets of Montreal and the arrest of hundreds of people. In response Laporte was killed by his abductors. James Cross remained in captivity for another seven weeks – at one point he was even reported to be dead -- until police finally located the gang’s hideout and negotiated an end to the crisis.

What have these events to do with Vancouver? Five days after Laporte was taken, city mayor Tom Campbell appeared in public flanked by a pair of armed security guards. The October Crisis had reached right across the country. Local authorities had received threats from FLQ sympathizers on the West Coast warning that they intended to take the mayor captive.

Unlikely as this plot sounded, Campbell took it seriously indeed. Interviewed by a television reporter, he stared solemnly into the camera and told the public that he had left orders that if he was taken, no ransom should be paid. “I’ll take my chances,” said the mayor, putting on his bravest face. He also used the opportunity to lobby for more police powers, including the right to enter homes without a warrant.

When the War Measures Act came into effect it gave arbitrary power to police right across Canada, not just in Quebec, and Mayor Campbell warned that he was going to use it not against terrorists but against hippies and layabouts, who he was fond of describing as “parasites on the community.”

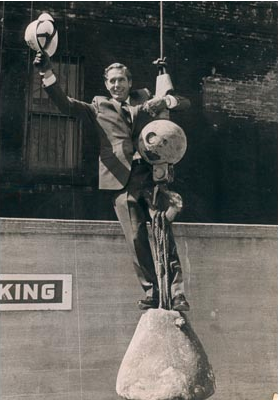

By this time Campbell had been in office for four years. He was equally unrestrained when clearing the hippies off the streets as he was trying to demolish much of the downtown to make way for a new freeway. An iconic image from the era shows him waving a hard hat as he swings through the air on a wrecking ball (see above). His disdain for the youth subculture, for left-wingers, really for anyone who opposed his grandiose plans for the city, was invariably expressed in colourful language. He described opponents of one of his schemes as “Maoists, Communists, pinkos, left-wingers and hamburgers” (hamburgers, he explained, being people without university degrees). One of his favourite targets was the underground newspaper, the Georgia Straight, which he tried many times without success to chase off the streets.

Prime Minister Trudeau may not have intended it but his suspension of civil liberties gave Mayor Campbell one more tool in this war on the hippies and the yippies (seven members of the Vancouver Liberation Front were thrown in jail for distributing copies of the FLQ manifesto) though the crisis passed before he could do too much damage.

Campbell was in some ways a comical character, but his period in office – he retired before the 1972 election -- marked a critical turning point in Vancouver politics. By opposing many of his schemes the public showed it was no longer willing to simply go along with what the “experts” advised and the developers wanted. Essentially there was a changing of the guard as the old elitist, backroom politics where the planner and the property developer were king was overthrown by a new politics of public participation and consultation. A new civic political party came into office and the dictatorial city planner was fired. As a result the 1970s was a far different decade than the one that preceded it.