My friend Gil Hewlett passed away the other day. He was 80.

Gil was a respected marine scientist who grew up in Lake Cowichan on Vancouver Island. He told the story of walking past the Vancouver Aquarium one day when he was a young man arguing with himself about what to do with the rest of his life. This was 1964 when the Aquarium was just getting into orca research. Gil went inside to take a look and fell to talking with the facility’s legendary director Murray Newman. Long story short, Gil ended up spending his entire career working there.

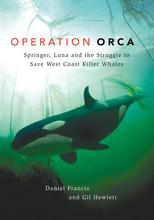

I met Gil fifteen years ago when the Aquarium hired me to write about Springer, the young orca relocated from the Seattle area back to the Johnstone Strait area. For the first time an orca was reunited with its family in the wild. Gil had compiled a ton of research about the episode and the Aquarium needed a writer to fashion it into a book. Gil had been diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa when he was a teenager and had been steadily losing his sight over the years. When we met he was completely sightless and on the verge of retirement.

I once asked Gil what he thought I looked like. Naively I thought my voice and general presence might have provided him with some clues. But he claimed to have formed no impression of my appearance. Or perhaps he was too polite to say. I often pestered Gil with questions like this about how he experienced the world. He was tolerant of my curiosity, as he was resigned to his disability, though he said that it had not always been so, that as he lost the final vestiges of his vision he was bitter and depressed and difficult to live with. Somehow he came to terms with what life had dealt him. The Gil I knew was cheerful, modest, curious about others, optimistic and thankful for his family and his long career at the Aquarium.

When our book appeared the publisher sent us on a road trip. We put together a public lecture and slide show which we delivered at several locations on Vancouver Island. The first stop was Port Alberni where we appeared at a local bookstore. No one turned up to hear us. I mean that literally. Not a soul, aside from our wives. We decided to go ahead anyway, figuring we could use the practice. We’d worked up a routine where I would introduce each slide, describing the Springer saga, then Gil would take over with his vast knowledge of the whales and the people and places involved.

By the end of the tour we were working smoothly together and attracting audiences in the hundreds. At one stop a fellow came up to me after the presentation and asked: “What Einstein thought it would be a good idea to ask a blind man to do a slide show?” But in fact it was apparent to me that in many cases people were not even aware that Gil could not see.

The final show was in Telegraph Cove, the whale-watching capital of the south coast. Dozens of Gil’s friends from the scientific community showed up, eager to see him and, I felt, to honour his contribution to the field. It was a special evening.

Toward the end of his life Gil was suffering from dementia and living in a care facility. The pandemic was hard on him but he never gave up cracking his corny jokes and being interested in the wider world, even as he admitted that later he would not remember a single word of what we talked about. His death was unexpected, but peaceful.

During that visit to Telegraph Cove I was sitting in the visitor’s centre on the dock selling copies of our book when a man from Great Britain came in with his two young daughters. They had just disembarked from the whale-watching boat. The man told me that when his youngest girl had become interested in whales he went online to find out where was the best place to see them in the wild. He was told that place was Telegraph Cove so they had come all the way from England to go out on the water and get a look. They had just seen several orca and one or two humpback and the girls were vibrating with excitement. Not for the first time I was witnessing the intense feelings whales arouse in their human compatriots.

So much that we know about the orcas we know because of the ground-breaking work that people like Gil and his colleagues accomplished since the 1960s. Not a bad legacy to leave behind.